CNN vs transformer model difference in image processing

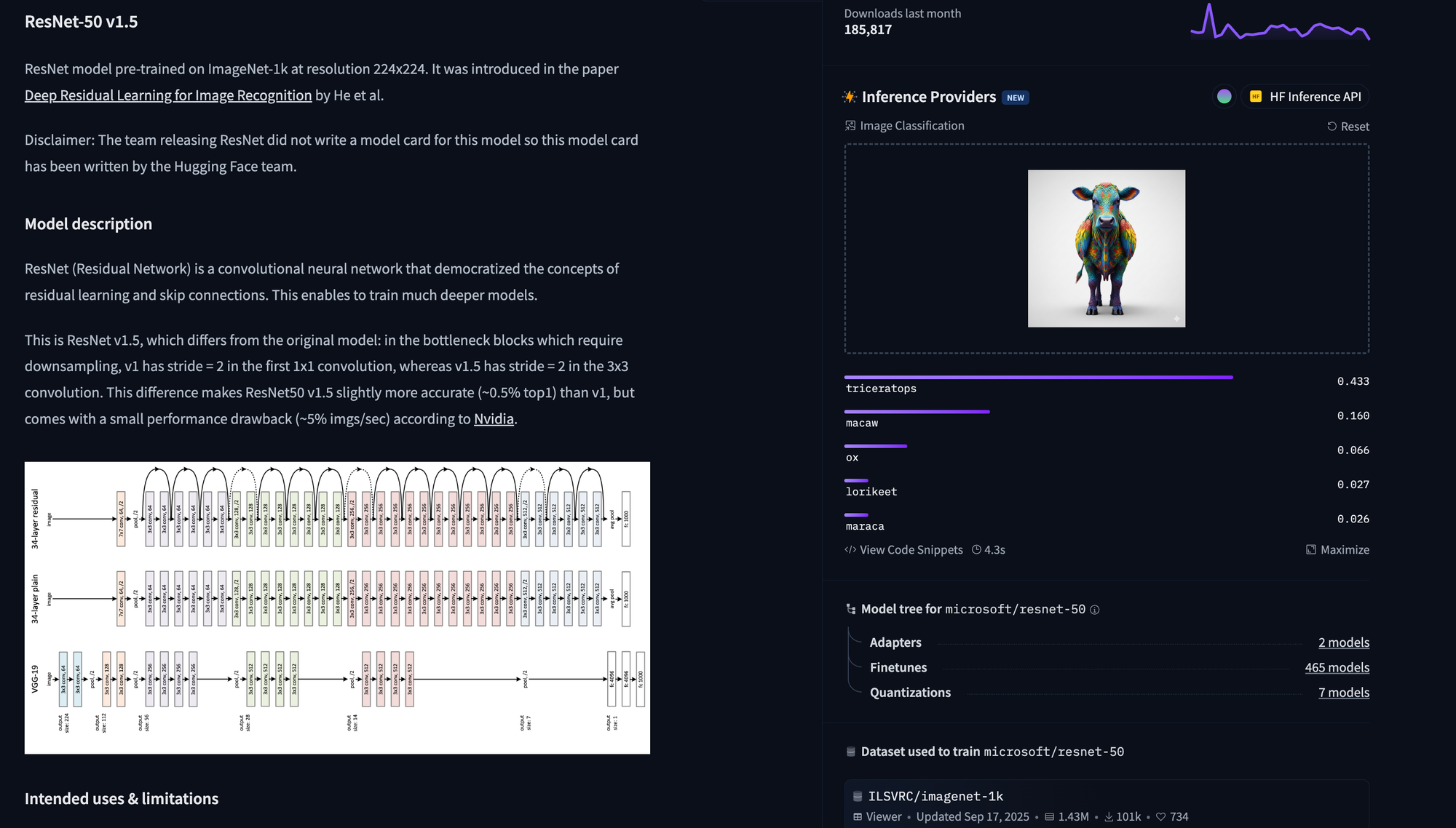

Let's start with an interesting experiment. Here is a Gemni-generated cow (above) with macaw feathers as the texture. Is it a cow or a Macaw?

We used two vision models: ResNet and ViT to figure out what it is

Let's start with ResNet:

I am not sure where the Triceratops comes from, but Macaw is a plausible guess.

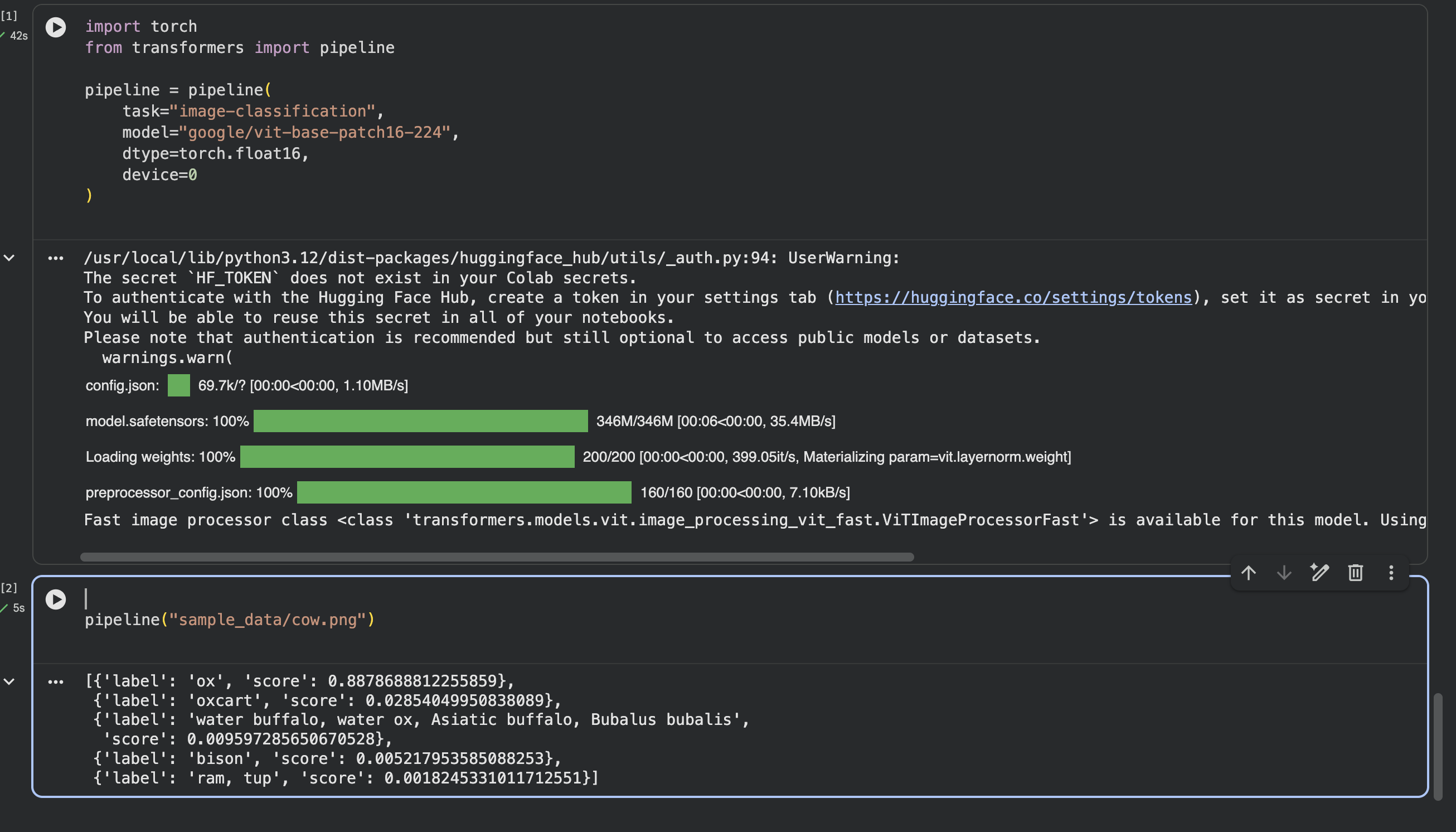

Then we used ViT:

It identifies it as an Ox, very close to a Cow.

So why do these two models differ so much? I guess when you look at this image locally or globally you have reach different conclusions. That pretty much summarizes how these two renowned vision models differ.

But let's not stop at the punchline. Let's dig into why these two architectures see the world so differently. Understanding the mechanics behind CNNs and Vision Transformers (ViTs) reveals a fascinating shift in how machines learn to interpret images.

How CNNs See Images: from local to global

A Convolutional Neural Network processes an image the way you might examine a painting up close with a magnifying glass. It starts by scanning small regions of the image, one patch at a time, looking for simple patterns like edges, corners, and color gradients. These small scanning windows are called filters (or kernels), and they typically start at sizes like 3x3 or 5x5 pixels.

Think of it this way: imagine looking at our colorful feathered cow through a tiny window that only shows a 3x3 pixel area. At that scale, all you see is a patch of bright feather texture. You have no idea whether you're looking at a cow, a parrot, or a piece of abstract art. That's how a CNN's first layer works. It's focuses on the local patches.

Layer by Layer: From Edges to Objects

CNNs build understanding through a hierarchy of layers, and this is key to their design. Here's how the progression works in a model like ResNet:

Early layers detect low-level features: edges, color blobs, and simple textures. A filter might learn to fire when it sees a horizontal edge or a green-to-blue gradient. Middle layers combine those low-level features into parts: an eye shape, a feather pattern, a curved horn. Deep layers assemble parts into whole objects: "this collection of shapes and textures looks like a bird" or "this looks like a cow."

This hierarchical approach has an important consequence: each layer only sees a limited "receptive field" of the original image. The first convolutional layer might see a 3x3 region. After pooling and more convolutions, the next layer's neurons effectively "see" a 7x7 region, then 15x15, and so on. It takes many layers before the network can relate information from opposite corners of the image. In a deep model like ResNet-50 with its 50 layers, the receptive field gradually expands, but the process is inherently local-to-global.

This is why ResNet saw our feathered cow and thought "Triceratops" and "Macaw." The colorful feather textures dominated the local features that ResNet was aggregating. The bright, iridescent patterns screamed "bird plumage" at every layer, and the unusual shape features confused it into exotic animal categories. The actual cow-like body shape, the context of the whole figure standing on four legs, these global cues got lost in the noise of overwhelming local texture signals.

How Vision Transformers See Images: global attentions

Vision Transformers take a fundamentally different approach. Instead of scanning the image with small sliding filters, a ViT chops the entire image into fixed-size patches (typically 16x16 pixels) and treats each patch like a "word" in a sentence. If you have a 224x224 pixel image and use 16x16 patches, you get 196 patches total, arranged in a 14x14 grid.

Each patch is then flattened and projected into an embedding vector, just like how words become embeddings in a language model. These patch embeddings are fed into a Transformer encoder, and here's where the magic happens: self-attention.

Self-Attention: every patch tries to relate to other patches

In self-attention, every patch computes a relationship score with every other patch in the image, in a single layer. This is the critical difference from CNNs. There's no need to wait for information to propagate through dozens of layers. From the very first Transformer layer, patch #1 (top-left corner of the image) can directly attend to patch #196 (bottom-right corner). The model immediately has a global view.

Here's a simplified version of how self-attention works for each patch: the model generates three vectors from each patch embedding, called Query (Q), Key (K), and Value (V) (this notion came from the original paper Attention is All you Need, published by Google, which is a search engine, thus query). The Query of one patch is compared against the Keys of all other patches to produce attention weights. These weights determine how much each patch should "pay attention" to every other patch. The final output for each patch is a weighted sum of the values of all patches.

In plain English: each patch asks "which other patches in this image are most relevant to understanding what I am?" The patch showing a cow's ear might attend strongly to the patches showing the cow's eyes and nose, even if those are on the opposite side of the image. This allows ViT to understand overall shape and structure from the very beginning.

Multi-Head Attention: Multiple Perspectives at Once

ViT doesn't just run one round of attention. It uses multi-head attention, where the standard ViT-Base model runs 12 attention heads in parallel within each layer. Each head independently learns to focus on different types of relationships. One head might specialize in tracking spatial relationships (patches that are near each other), another might focus on color similarity, another on texture contrast, and yet another on structural patterns like symmetry.

With 12 heads across 12 Transformer layers (in ViT-Base), the model runs 144 different attention operations total. Each one captures a different slice of the global relationship map. The results from all heads are concatenated and projected back into a single representation. It's like having 12 expert analysts each independently studying the same image from different angles, then combining their findings.

This is exactly why ViT looked at the same feathered cow and said "Ox" (88% confidence). Despite the wild feather textures, the attention mechanism could look past the local texture noise and focus on the global shape: four legs, a bovine head shape, the proportions of the body, the stance. The overall structure says "this is clearly a bovine animal" regardless of what the surface texture looks like.

Differences in summary

Let's summarize the fundamental architectural differences between these two approaches:

| Aspect | CNN (e.g., ResNet) | Vision Transformer (ViT) |

|---|---|---|

| Input Processing | Sliding 3x3 or 5x5 filters over raw pixels | Image split into 16x16 patches, treated as sequence |

| Receptive Field | Local → gradually expands over many layers | Global from the very first layer |

| Key Operation | Convolution (local feature extraction) | Self-attention (global relationship mapping) |

| Classification Bias | Texture-biased | Shape-biased (more human-like) |

| Spatial Awareness | Built-in (inherent to convolution) | Learned via positional embeddings |

| Data Requirements | Works well with smaller datasets | Needs large datasets or pre-training |

Input processing is fundamentally different. A CNN slides small filters across the raw pixels, processing overlapping regions sequentially. A ViT slices the image into a grid of non-overlapping patches and processes them all simultaneously as a sequence, much like words in a sentence.

Feature scope is the core distinction. CNNs have a small receptive field that gradually expands over many layers, building local-to-global understanding. ViTs have a global receptive field from layer one, as every patch attends to every other patch through self-attention.

Spatial awareness works differently in each architecture. CNNs have built-in spatial inductive bias because the convolution operation inherently preserves spatial locality; neighboring pixels are processed together. ViTs have no inherent spatial awareness and must learn spatial relationships from positional embeddings that are added to each patch, telling the model "this patch came from row 3, column 7."

Texture vs. shape bias is perhaps the most practically important difference. Research has consistently shown that CNNs are heavily biased toward textures when classifying images. ViTs, by contrast, develop a stronger shape bias, more similar to how humans perceive objects. We recognize a cow by its shape, not by its skin texture, and ViTs tend to do the same. This is exactly what we saw in our experiment above.

Data hunger is a practical trade-off. CNNs, with their built-in spatial assumptions, can learn effectively from smaller datasets. ViTs, which must learn everything from scratch including spatial relationships, typically need much larger training datasets or pre-training strategies (like training on ImageNet-21K or using self-supervised methods) to reach their potential.

Who is right?

Imagine you're trying to identify a building from a photograph. A CNN is like an inspector who starts by examining individual bricks, then notices the windows, then the floors, and after many steps, finally puts together that it's a Gothic cathedral. A Vision Transformer is like someone standing across the street who immediately sees the whole building, notices the pointed arches relate to the flying buttresses, sees how the rose window connects to the overall facade, and says "Gothic cathedral" right away. Neither approach is wrong, they just prioritize different types of information. In our case, it is neither a cow/ox nor a macaw.

Where Does This Leave Us?

The shift from CNNs to Vision Transformers represents a philosophical change in how we approach computer vision. CNNs were inspired by the visual cortex: process locally, build up to global. ViTs were inspired by language models: treat visual information as a sequence and let the model figure out all relationships through attention.

In practice, the industry has moved heavily toward Transformer-based architectures, and for good reason. The global attention mechanism produces more robust representations that generalize better, are less susceptible to texture-based shortcuts, and align more closely with human visual understanding. That said, CNNs haven't disappeared. Hybrid architectures that combine CNN-like local feature extraction with Transformer-style global attention are becoming popular, with models like Swin Transformer borrowing ideas from both worlds.

As our colorful cow experiment demonstrated: when you look at the world locally, textures dominate your judgment. When you look at it globally, shape and structure win. Vision Transformers proved that sometimes, stepping back and seeing the big picture is exactly what you need to get the right answer.